2020 in Review: Pakistani Students and the Pandemic

BlogPublished Date:

By Asiya Jawed and Haleema Hasan

|

| Students in Karachi stage a protest against online classes Source: Scroll.in |

In April 2020, a month after the first coronavirus cases were detected, 300,000 schools closed in Pakistan and 46 million Pakistani students were forced to stay at home. Almost six months later, schools had only partially opened whilst students and teachers were still acquainting themselves with online learning methods.

|

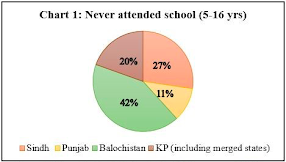

| Source: Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement 2018-19 |

In this blog we review what 2020 looked like for Pakistani students, exploring the intricacies of class, gender and ethnicity amidst a raging pandemic. The year also saw consistent protests, struggles for student unions and politicization of students’ demands. As with its impacts on other segments of society, the pandemic’s impact on students has been defined by their varying vulnerabilities and privileges, and the ways that these intersect.

|

| Source: Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measu |

Class

|

| Source: UNICEF, World Bank |

The virus impacted students from low socio-economic backgrounds the most. The poorest households have the least access to education as the proportion of out-of-school children is highest in the lowest income quintile and rich households are more likely to use technology. Most Pakistani students can’t afford internet services or live in remote localities without reception. Despite these circumstances, educational institutions and the state chose to conduct online examinations and charge full fees even when students weren’t occupying campus spaces.

Online learning became a logistical hassle for many living in remote and underdeveloped areas. An academic at University of Sindh, Jamshoro was shocked when she saw students in mud houses or sitting under trees to attend their online classes. At times she saw her female students sitting on the stairs in their houses because they didn’t have a private space without any noise. Substantial class differences heighten the disparities within the education sector, and female students are at a greater disadvantage.

Gender

After schools shut down, girls shouldered most of the work in the household or faced the risk of being forcefully married. However, this discriminatory period became a catalyst for several female students to voice their concerns. One of the most pertinent problems that female students raised through offline and online protests was on-going sexual harassment in educational settings.

In November 2020, students of Karakoram International University (KIU) registered harassment complaints against the university’s scholarship officer but were instead booked on different charges and two of them even arrested. Although 300 students protested outside the Vice Chancellor’s (VC) office, they didn’t receive justice. The VC took notice of the complaints and set up a committee to probe the incident but there are many problems with such committees too. Rai Ali, a student leader, shared with us, “Female students have to be in rooms full of men and narrate what happened to them which can be an intimidating experience in itself as some of the men in those rooms would end up harassing the victim again.”

Just ten days before the KIU protest, female students studying in Islamia College Peshawar complained that the faculty and staff of the institution were sending them vulgar text messages, and harassing them under the garb of checking academic work. They held a “Girls Walk Against Harassment”, demanding the university to appoint a local person to address these complaints and the present committee to function in-line with the Harassment at the Workplace Act 2010. Other students utilized online platforms to address several harassment cases in elite institutes such as Lahore Grammar School (LGS) and Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS).

However, lack of gender justice in Pakistan transcends class privilege. Using online platforms has been risky for students as defamation laws are used in response to #MeToo. LUMS allegedly has a history of threatening women in such cases, with a student rightfully questioning, “[T]ell me — where do we go if not online? Who is there to listen to us?” While alumna of the school complained that the Office of Student Affairs discourages victims to file official complaints, it is also important to use existing accountability mechanisms in order to strengthen them. School administrations must understand the backlash and trauma that female students face when they come forward to complain, and build gender-sensitive committees with student representatives.

Ethnicity and Locality

|

| Source: Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement 2018-19 |

|

| Source: Who Can Work and Study From Home in Pakistan: Evidence From a 2018-2019 Nationwide Household Survey |

|

| Source: Constitution of Pakistan |

Against the backdrop of staggering inequalities and a pandemic, students eventually resorted to protesting for their rights. In June, several of them were arrested for protesting in Quetta against HEC’s decision to conduct online classes despite structural failures such as power cuts and extreme dearth of internet facilities. The situation is worse for minorities like the Hazaras and those living in conflict-ridden areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) where political violence and deliberate state security measures have created conditions similar to lockdowns and quarantines long before the pandemic. Critics and protesters argue that the continuing suspension of the internet especially amidst shifts to online education are a violation of the constitutional Right to Education.

|

| Source: The Diplomat, The News, Slate |

Floods during the pandemic severely impacted rural Sindh’s already flailing education system with a massive power outage and schools used as shelters. In Punjab, there are glaring differences between the northern and southern districts with the latter performing very poorly in most education indicators. COVID-19 is worsening the situation in these areas. Despite the infection risk, students and teachers are forced to go to urban areas as there are no internet services.

Apart from National Cash Transfer schemes, little has been done specifically for these areas. The authorities responded to protesting students by mostly engaging in violence. Dismayed by the outcome, students filed petitions in high courts across Pakistan, which directed the Balochistan government to form a committee to address students’ issues. The government also requested the KP high court to restore internet connections but no action on either order has been reported yet.

There were some hopeful instances in these circumstances as well; Zong Pakistan secured a contract with Universal Service Fund to provide high speed internet in some areas of rural Balochistan; In KP, UNICEF’s advocacy led to the development of online resources and better implementation of offline learning for students; rural Sindh has been reportedly more receptive to social distancing than urban areas and a radio is being leveraged there to discuss psychological wellbeing during the pandemic. Finally, the Punjab government has legally banned withdrawing South Punjab’s Annual Development Funds which were recently increased by 35%.

Intersections

These ethnically charged, gendered and class-oriented vulnerabilities do not operate in isolation. They are inextricably linked and exacerbate the impact of an event as severe as a pandemic. Baloch students not only face a dismal educational landscape but also financial constraints in accessing any available opportunities. The seats reserved for them in universities of Punjab were withdrawn and scholarships suspended between 2017 and 2020 amidst rising tuition fees and education transitioning online. After a students’ protest march in October 2020, the Governor of Punjab announced full and partial scholarships annually available to 3, 200 students from Balochistan, KP and Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) at varsities in Punjab. Although hopeful, we are yet to see these plans materialize.

|

| Source: The Express Tribune, The Nation, The News, Twitter |

Amongst students from these localities and class backgrounds, women are at a further disadvantage. For instance, in Sindh, less than 10% of tertiary students are women. The government also has a class-based response to harassment cases. The Punjab School Education Minister promised to deal with harassment complaints by LGS students personally and the Minister of Human Rights took notice of the allegations at the two “premier private institutions”. After students and alumna conducted a sustained online campaign, four employees of LGS were terminated while students from public universities were ignored, vilified or arrested.

Politicizing Students’ Vulnerabilities

Students demands and actions were often politicized by both the incumbent government and the opposition for their political expediency. While PPP Chairman Bilawal Bhutto supported MDCAT students, criticizing Pakistan Medical Council’s bureaucratic inefficiencies, PML-N leader Maryam Nawaz attended Baloch students’ protest. Both are part of the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM), an alliance of 11 opposition parties formed in September 2020. Our interview with Rai Ali revealed that shrinking civic space has forced students to turn to PDM even though they suspect the alliance will remain anti-establishment only until it assumes power itself.

Recommendations and Conclusion

|

| Source: BBC |

It has been a long, trying year for students. However, trying situations are also opportunities for imagining better systems. Some ways to further affect change in the education sector include supporting the ed-tech industry, crowdsourcing and curating content akin to the Spanish Ministry of Education, further scaling up the use of radio for education, and investing in public-private partnerships similar to the model in Uruguay. Additionally, Mexico’s Telesecundaria is a good example for Pakistan to improve the quality of the Teleschool which was widely available but incomprehensible.

|

| Source: Budget 2020-2021 |

However, any response strategy is incomplete without addressing the demand for student unions. In 1984, student unions were banned because of their progressive work for students and the wider civil body. The pandemic has intensified the students’ perpetual need for a collective space. Rai highlights, “The teachers in our university have a union, the guards have a union but the only union that is missing is the student union… there are 95% students in a university but those 95% aren't given a chance to represent themselves.”

|

| Source aku.edu |

For students, 2020 has been rife with uncertainty, learning losses and protests. As their problems spiralled, Covid-19 became an impetus for them to push for their rights. However, their demands haven’t been fully addressed despite consistent activism. It is imperative that the state revives student unions, invests in long-term solutions and addresses the inequities marring the education sector now more than ever.